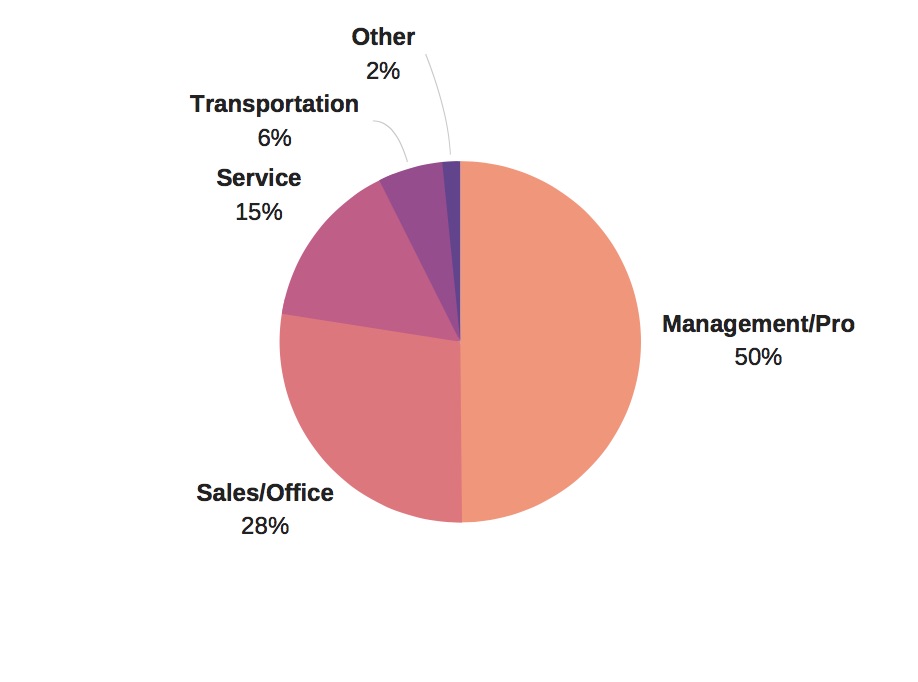

Percent of female veterans employment distribution

As veterans make their transitions into civilian life, it often gets overlooked, the path they took to get there. Many have dedicated portions of their lives to the U.S. armed forces, while others used the time to fill a short part of a long career, but all veterans find their way back to everyday life.

In a census done by the Veteran Affairs, there have been over 41 million people who have served in an American war--dating from the American revolution in 1775 until today’s current campaign against global terror. Of those 41 million, 23 million are still living today, working in professional careers, raising families, and bringing together communities.

Elon Professor, Randy Piland, a Desert Storm Army Trooper Veteran and Army Photojournalist, resonates with the lack of services provided to older members of the military upon return home.

“When my brother, Emmet, returned home after a year of service in Vietnam, he was assigned to a base in Colorado where he had little to no duties assigned,” Piland said. “He and several others would be used to clean the barracks and other duties that had no real purpose...when requesting to go back to Vietnam, they couldn’t be guaranteed rejoining the unit until they were formerly assigned.”

Alex Luchsinger, a former member of the Marine Corps, Purple Heart Recipient and Elon University professor experienced some of the discharge services first hand, after his time serving in the military. After one too many close calls, according to Luchsinger, he chose to pursue civilian life, where he noticed a lack of diversity when it came to veteran services. What interests veterans, such as Luchsinger, is the resources provided to those who served in previous wars, compared to that of more recent veterans.

“I think that the government has gotten better at it (providing resources to veterans)," Luchsinger said. "When I got out it was kind of like, ‘See you later,”’.

“If you look at news, there is a lot of mess with the VA, which are supposed to provide the support and programs for veterans, but that varies from place to place," Luchsinger said. "There are 1,400 hospitals in the country, it's the largest hospital system in the country, but some can be very very good and others just abysmal.”

For veterans, the discharge process can be one filled with all kinds of emotions, experiences and obstacles which adds to the chaos that is coming from home.

"We never got real close in Vietnam. We didn’t call each other friends, we called each other buddies. Because a friend means you know a friend for life, buddies is just a term. If he gets blown away tomorrow you know that’s no big deal.”— Benny Kidd, Vietnam War veteran

When Benny Kidd first got drafted in 1969, he had a feeling he’d end up in Vietnam, but thought if he was lucky he’d end up being stationed stateside.

“That never happened,” he said. Instead, he came to grips with where he was headed and decided it was time to man up and serve his time.

“At the time that I was there, I didn’t know why,” he said. “The American people didn’t want us there, the Vietnamese people didn’t want us there. We darn sure didn’t want to be there, but we didn’t have much of a choice. But I think after coming home and looking back it was a good experience.”

Kidd considers the two years he spent in the war as some of the best years of his life because of the personal growth it sparked within him. He became more appreciative of the things he had by witnessing the Vietnamese people and how little they had.

“I don’t take life for granted because it can change at any time,” he said. "We never knew from one night to the next if the guy beside us was going to be there or not.”

But what he was able to take away from the experience did not translate to his home reception. People viewed him and other Vietnam veterans as menaces to society and it showed during their return to the states.

“We weren’t welcomed too much coming back home by the American people,” he said. "They told us the first chance we get take our uniforms off because they were waiting at the airport and everything spitting on us, calling us baby killers, throwing rocks at us, throwing defecate at us.”

That negative stigma followed throughout all areas of civilian life, including when trying to find work. According to Kidd, even just mentioning that you were a part of the war would cut job interviews short.

Eventually, Kidd was able to find stability in life through his job and family, but it did not come without personal complications from the war. Today, Kidd suffers from PTSD, a mild heart condition from agent orange exposure, poor hearing from rounds being shot and persistent night terrors.

“Certain smells, certain sounds trigger things that were happening,” he said. “[I have] trouble sleeping. I might get up three or four times during the night just to check the house just to make sure nobody’s in there and go on back to bed even though I hadn’t heard anything.”

One of the things Kidd says helps him the most is talking things out. Though he previously felt uncomfortable sharing stories about Vietnam, he now sees talking as “good therapy” and uses it as a method to get his feet back on the ground. Organizations like Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) have aided in the process.

For two years, Kidd has been a member of the VFW post in Burlington and describes its main goal as being committed to taking care of veterans who may have fallen on hard times or who may just need a hand. He recalls his challenges when returning home and feels that the VFW mission is to make sure that experience isn’t repeated.

“We don’t want ever, ever, ever again for a veteran to come home and be treated the way we were when we came home,” Kidd said.

It wasn’t until a good friend of his, Carl Norris, had mentioned the organization that Kidd even knew about the post. The two had known each other for years after meeting through their shared experience of having disabled children at the Arc of the United States, an organization dedicated to serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. After several conversations of getting to know each other, they learned they had both served time in the same war.

“I told him you need to be in the VFW, you’re a veteran,” Norris said. “And I finally told him, ‘Benny, if you come to a meeting I’ll pay your first year’s dues,’ and of course I was obligated to pay his dues for the first year. After that, he really took an interest and saw it as something he wanted to do. He’s gone on and worked very hard in the VFW and has been appointed to quartermaster.”

Norris sees the VFW as having helped Kidd’s PTSD by giving him a positive activity to focus on.

“If you’re involved in any activity, you won’t have time to think about that,” he said. “The VFW helps him do what he likes to do.”

Six VFW posts reside in Alamance County with roughly 240 members total. Kidd describes it as a place with good camaraderie that provides veterans with the services they need. It’s trying to stray away from its old stereotype of being a club-like scene for veterans.

“The mindset of the old VFW is that it’s a place where you go and sit down and drink beer and liquor and smoke cigarettes and talk old war stories to your buddies sitting there next to you,” Kidd said.

To change the way the community views the VFW, the Burlington post is actively working on becoming more family oriented by hosting special events for veteran parents to attend with their children.

With money raised over bingo nights as well as through membership dues, fundraising and occasional donations, the organization maintains itself as a resource in the veteran community.

According to Norris, Kidd’s involvement in VFW has been huge and has even surpassed his own. He keeps everyone up to date on the organization’s affairs, makes sure members are attending meetings and is at the post every day.

“I’ve never seen anyone who didn’t like Benny,” Norris said. “It seems like everybody who comes in knows Benny Kidd.”

“I went over there when I was 20 years old. I did not know whether I would be back or not by the time I turned 21.”– Ron Allred, Vietnam War veteran

It was at the age of 20 when Ron Allred decided he wanted to serve his country. While many were drafted, Allred volunteered to serve. After receiving his basic training in Lackland, Texas, he went on to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was placed in the personnel field. One year later, he decided that he wanted to go to Vietnam.

“Allred was first sent to Tan Son Nhut Air base in Saigon, before becoming a guard. He was stationed at Tuy Wha, an American Air Force Base; Bien Hoa, the Vietnam People's Air Force military airfield; and Cam Ranh Bay, the major port of entry for U.S. military supplies and personnel in South Vietnam.

As a guard, Allred was responsible for providing security. Allred would guard the entrance point to the base or on search and destroy missions. He guarded ammunition dumps, bunkers, aircraft, and would go on “Med Cap missions,” which were medical unit missions, where security was provided to the doctors that would go out to the villages to provide medical service for the people.

“In Vietnam it was very dangerous, no one really wanted to have the duty of guarding the ammunition dump,” Allred said. “That would be one of the spots they wanted to hit.”

He spent a year as a guard overseas before returning back home. Allred considers his time in the military as a time he will never forget.

Allred doesn’t consider his experience of returning to regular American life to have been difficult, except for getting off of the plane after his discharge.

“This really affected me – we got off the plane and walked across the tarmac. To have people standing there and spitting at you, it really made a lot of us really mad,” he said. “I did volunteer to do that, but to have people stand there and treat us that way, and call us baby killers and things of this nature, it just wasn’t right. It wasn’t right.”

Besides his negative public acceptance, Allred didn’t suffer much from PTSD.

“I did not have a lot of dreams or anything like that,” he said. “I wasn't out in the field all the time so my heart really goes out to my brothers and sisters who are having to fight in other areas out in the field.”

Allred spends time at the American Legion in Burlington, NC

As a guard, Allred was placed in Cam Ranh Bay for most of his tour, a base on the ocean known to have the best security around.

“Lucky. I was very very lucky,” he said. “A lot of the people that were out in the field, they looked at Cam Ranh Bay as being an R&R center for them.”

While his mental state didn’t suffer, Allred did fall prey to some medical issues. The cause: Agent Orange, a herbicide used to eliminate forest cover and crops for North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops. Up to four million people in Vietnam were exposed to the chemical, and it has been found to cause numerous health complications.

“It is a killer. I contracted Agent Orange when I was over there and it messed my blood up to the point where it’s supposedly affected my heart. Because of that I have had numerous heart attacks, and, as a matter of fact, I had one just a few weeks ago,” he said.

Allred is now considered to be 100 percent disabled. He has had at least five heart attacks along with open heart surgery. He takes 12 pills every morning and night, with three in the middle of the day. Being fully disabled, Allred receives free medical care through the Veterans Association. He says he is fully satisfied with his medical care.

“It provided these glasses for me for free, and now they’re saying something about possibly having someone come into my household and clean it up and possibly even do some cooking for me because right now I go out to buy all my food - I can’t get around too good,” Allred said.

“The American Legion is a great organization. What we do is help the community. That’s what the American Legion is for. We try to provide help to our community in anyway we can. In fact, all the other organizations are somewhat the same,” he said.

Karen Spoon works closely with Allred, as the lounge manager for the American Legion, a place she’s worked at for nearly 20 years.

“It’s like a family, and we do as much for veterans as we can–you know, to help them if we can. It’s a social group, really,” Spoon said. “This is basically a social club for them. But we do handle some of their problems, if they have anything.”

Spoon’s husband was a member before moving away, but she has remained. She started out as a volunteer, and has held offices with the American Legion Auxiliary before now working with the American Legion.

The American Legion family in Burlington, NC has grown to 214 members. Allred joined the American Legion about five years ago, and said it has given him countless benefits.

“I haven't been a member as long as a lot of people, but I had other things to do with my life I thought. But I made a mistake. I should've joined the organization years and years ago,” he said. “I don't know why a vet would not want to be a part of one of the organizations. I mean, they have a lot of benefits for them - different benefits for the different organizations.”

Spoon said people call around the holidays asking for help.

“I think there’s a lot of lonely people around the holidays, and they don’t have the funds to do the things that they would like to, so we try to help in that way,” she said. “We try to have fun. It’s a means of fun; it’s a means of the guys to come and talk over stories if they want to. And there’s a lot of them that do come in and they just want to sit and talk and just relax for a while.”

Not only is Allred the senior vice commander at the American Legion in Burlington, NC, but he is also the junior vice commander of the VFW in Gibsonville. He can be spotted helping out at bingo every Tuesday, and for the American Legion’s family Easter egg hunt he held the star role: the Easter bunny. For Allred, giving back to fellow veterans it what makes his post-service life easy and rewarding.

“I volunteer for stuff all the time because I enjoy doing it,” he said. “When I am able to help someone, it gives me a good feeling.”

“Everyone else that was there didn’t suffer physically inside the skull from the IEDs, but a lot of those guys suffer more from PTSD than even I did because they witnessed...It’s almost like a dream to me whereas those guys, it’s reality.”– Garrett Carnes, post-9/11 Veteran

“My father was a Marine stationed in Camp Lejeune, so I kind of grew up there and was around the Marine Corps culture my entire life. And I’ve known for as long as I can remember that that’s what I wanted to do,” said veteran Marine Garrett Carnes.

The morning of February 19, 2012, Carnes and some of his corpsmen entered a compound and swept the area with metal detectors, continuing when no metal signatures were detected. Moments later, he stepped on an improvised explosive device (IED).

He said the IEDs contained carbon rods—which have a lower metal signature than aluminum or steel—and were able to pass unnoticed by their detectors.

“On the spot of the injury, I pulled my own tourniquets out and started applying my own tourniquets to try and stop the bleeding. When your femoral artery is severed, you have about 90 seconds before you bleed out and you’re considered dead,” Carnes said. “When all those Marines around me were injured from the blast, they couldn’t run over to me and start applying aid right away, because there’s so much dust in the air you don’t know who it is that’s injured.”

His legs were amputated on the scene, but 22-year-old Carnes’ immediate action saved his own life.

After the explosion, Carnes was flown to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, where he spent 18 months, still enlisted as a Marine.

Each day, he was taken from three to six appointments with various doctors and physicians throughout the hospital.

“From the inside, it is the most inspirational place, I think, in the world. Because you do have guys that have horrible, horrible wounds of war that they are walking around with—and that they will walk around with forever—but everywhere you went, there was a smile on these guys’ faces,” Carnes said. “They were happy, they were laughing.”

While Carnes credits the hospital for their hard work, he gives equal credit to his wife.

“She sat there with her log book like a Marine and noted every single thing,” he said. “She handled it like a medical professional herself, because, at one point, she was kind of my—almost like a general power of attorney over me. She had total control over me and, like a guardian angel, she made sure everything went according to plan and went right.”

Despite his extended stay in the hospital, Carnes said it strengthened his relationship with his wife.

“Public speaking I got into by accident when I was at Walter Reed. The Marine Corps, it grooms you to be public speakers,” Carnes said. “I don’t believe that you have it or you don’t. It’s a trained skill.”

Carnes said the Corps trained him to be a public speaker. Marines in leadership positions are constantly giving briefs to people in your own peer group, and to those above and below you.

In the hospital, he said there were times they needed a certain number of people to go speak to schools of new officers at Quantico. At first, he volunteered to go; a few times later, he looked at the schedule and asked to go speak at certain schools.

“You’re not going to reach every single person with the words that you speak, but if you can impact at least one person, that’s a pretty good rate, I think. So I was able to, hopefully, impact some of these Marines’ lives,” he said. “I was using it as a therapy point for myself, up onstage, to speak to these guys.”

Carnes said that when he came home to Alamance County, he discovered that word had gotten out about his speaking and a few schools in the area reached out to him and asked him to speak to their students.

While still adjusting to his home in a new county, Carnes was honored as part of a Homes for Our Troops event. At the event, Carnes met Stephen Baker, president of Resource Exchange Association (REA), a non-profit organization in Burlington, NC. Carnes was a recipient of REA’s REAch Wounded Warrior Toolbox Program, where toolboxes containing a few essential tools are delivered to post- 9/11 veterans.

“I met him at that first ceremony, and then I went to another ceremony where he was at supporting another veteran for Homes for Our Troops and I went up and reconnected with him,” Baker said.

Carnes and Baker spend time practicing their hunting skills together.

Carnes mentioned his public speaking hobby and, after speaking briefly at the event became an on-the-spot job interview for REA, he ended up running the toolbox program for three months, getting to know more about REA and Baker.

“Very loyal—he would do anything in this world for you, no questions asked. No matter what time of the day or what time of night, if I called him, he would be the first one that would be there,” Baker said.

Baker said the two are gym partners in addition to being friends. He calls Carnes a role model, both for himself and his daughter

Despite forever changing his life, Carnes says he would do everything all over again, including stepping on the bomb.